Does every Jewish mother want her son to become a doctor? Not always. If you’re a member of the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Israel, where many young men are expected to spend their days learning Torah full-time, many mothers in these communities would much rather say, “my son the rabbi” than “my son the doctor.”

Article by Sam Sokol, published on Forward.com on July 3, 2019.

Meet Israel’s First Hasidic Med School Student

Meet Israel’s First Hasidic Med School Student

And while there are ultra-Orthodox doctors, many of whom immigrated from abroad or found religion later in life, a Hasidic doctor who grew up in a local Hasidic community is as rare as a unicorn.

For Yehuda Sabiner, the path to medical school was an unorthodox one. The son of the dean of a Hasidic Gur yeshiva in Jerusalem, Sabiner, now a 29-year-old father of three, said that he has wanted to enter the medical profession since he was four years old when he innocently asked his paediatrician what he would have to do to become an MD.

When he told his parents that he wanted to be a doctor, they saw it “as a cute thing that children say,” he recalled. But when he continued insisting on his chosen profession at age 16, it ceased being amusing and became a source of concern for members of his family.

Sam Sokol

Sam Sokol

“As I grew up, I saw you can do it as a religious mission, as hesed [lovingkindness], which is very important part of the Jewish tradition. My mother had tears in eyes and said ‘I thought we passed the hard times,’” Sabiner told the Forward. But as he continued in yeshiva, getting high marks in Talmud and appearing to be on track to eventually become a rabbi or a religious court judge, his parents began to relax, although he would occasionally bring up the subject of medicine throughout.

While the ultra-Orthodox world is anything but monolithic, its overall workforce participation is significantly lower than in the national-religious and secular sectors, and many members of the most fervent Haredi communities shun secular studies and higher education.

According to figures released by the Israel Democracy Institute in December, some 45 percent of Haredim live in poverty and just under half of Haredi men are unemployed. Employment figures tend to be lower among members of “Lithuanian” or non-Hasidic Haredim. Despite these figures, however, there has been an increase in the number of Haredim studying for professional careers and the average Haredi monthly income increased by eight percent between 2015-16, “reflect[ing] a rise in ultra-Orthodox salaries among those employed,” according to the IDI. These gains can be credited to the “rise in the number of well-educated members of the ultra-Orthodox community and the advancement of ultra-Orthodox workers in the labor market (as a result of a combination of appropriate skills and education, and government programs).”

Sabiner’s dreams did not fade after his marriage. When he again announced that he intended to become a doctor, his parents replied that it was an issue for him and his wife to handle, while his new bride broke out crying.

“It almost destroyed our marriage,” he recalled, describing how her wife had thought she was marrying a future rabbi.

However, she soon had a change of heart and “came to me with tears in eyes, still upset, and said she won’t be the one to destroy my dream.”

Enrolling in a academic preparatory program run by the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Sabiner worked hard to make up all of the education that he missed attending a Haredi school. “I didn’t know anything, even the ABCs, [certainly] not to write or read in English,” he said. Studying late into the night, his wife helping him, and he gradually began to approach the level of education necessary to undertake medical studies.

After he left the Technion’s Haredi program and integrated into their primary track together with secular students, social life was initially awkward but he was soon accepted by his peers as just another student.

“The beginning was very strange,” he recalled. “It already began in the entrance of the building. The guard stopped me and wouldn’t let me go in: ‘What are you doing here?’ Girls were terrified to sit next to me, but after two weeks the ice melted and I have probably the best fiends of my lifetime here.”

Back in the Hasidic community, Sabiner initially kept his studies secret, but after he let the cat out of the bag he said he was surprised by the response.

“I give classes in my shul about halacha and ethics and medicine,” he said. “I cannot say that I’ve had any problems in the last couple of years.”

And despite their initial reluctance to support his dream, once he had chosen his path, Sabiner said that his parents became his biggest supporters, both financially and emotionally, giving him the breathing room to finish his studies.

Overall, he said, the majority of Gerrer Hasidim are in the workforce so his decision to work wasn’t as surprising to people as his choice of career, and he thinks that there is definitely a desire by many of his contemporaries to enter higher education and the professions.

Sam Sokol

Sam Sokol

“Almost from the beginning, I received emails and phone calls from the whole spectrum of the Haredi community, asking how to get into medical school,” he said, adding that he believes efforts to force the Haredim to include secular subjects in their school curricula would probably backfire. “Attempts to force change are creating a reaction of negativism and can destroy the willingness for revolution in our community. I really think it’s a process that’s continuing and we must minimize the intervention so that it will be successful.”

And despite their initial reluctance to support his dream, Sabiner’s parents have since become his biggest supporters, both financially and emotionally, giving him the breathing room to finish his studies.

Sabiner, who is in the final stages of his medical degree, has a message for his fellow Haredim.

“We are not cola bottles from the factory, where all the bottles come in the same shape and color. Everybody is an individual and if you want something you should dream the highest [dreams] and do your best to achieve it whether it’s being a rosh yeshiva or doctor or lawyer,” he said.

Sam Sokol is a freelance journalist based in Israel. A former Jerusalem Post and IBA News correspondent, he is the author of ‘Putin’s Hybrid War and the Jews: Antisemitism, Propaganda, and the Displacement of Ukrainian Jewry’.

JTA contributed to this report

This story “My Son The Doctor” was written by Sam Sokol.

I want to be a doctor, not a rabbi’: how Israeli ultra-Orthodox are being drawn into work. Traditionally, Haredi men have not joined the labour force. That is starting to change

Article by Harriet Sherwood, published on theguardian.com on September 10, 2018.

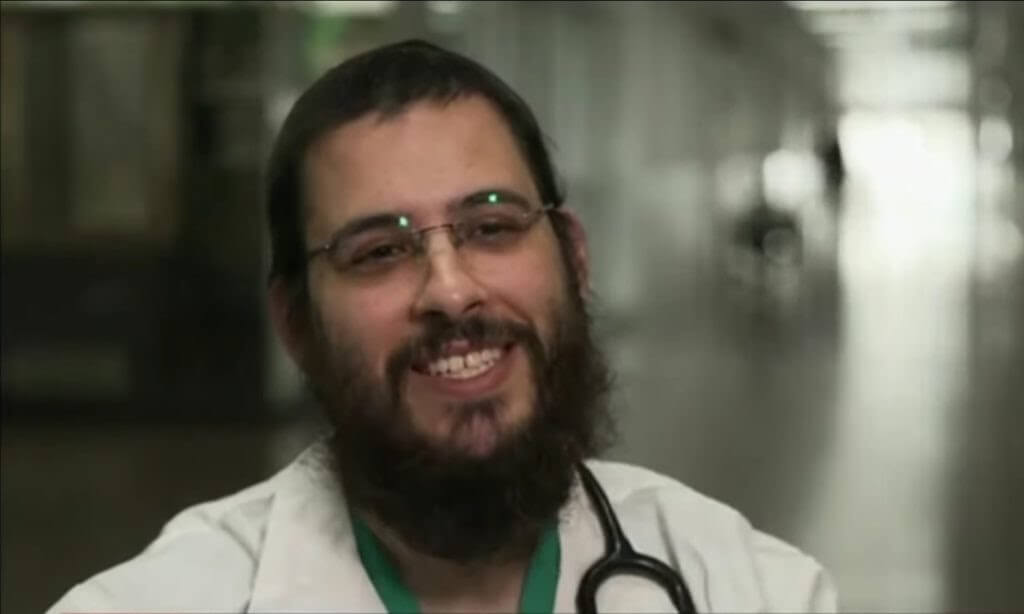

Medical student Yehuda Sabiner in class: ‘In the end 99% of people were encouraging me.’ Photograph: Rami Shlush

Medical student Yehuda Sabiner in class: ‘In the end 99% of people were encouraging me.’ Photograph: Rami Shlush

From the age of three, Yehuda Sabiner harboured a secret ambition to become a doctor. But it seemed unlikely to be fulfilled: he was raised in one of the strictest ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities in Israel.

His education was limited to religious study, first at a private school that barely taught mainstream subjects and later at a yeshiva, a religious school, where he spent 14 hours a day studying Jewish texts. Sabiner, a bright boy and an outstanding student, was earmarked to become a leading rabbi.

But he never forgot his dream. When he was 21 he confessed his ambition to his new wife. She was horrified: she had married him on the understanding that he would be a rabbinical leader. Also, he had no knowledge of science. But Sabiner’s yearning would not go away.

Now 28, Sabiner is embarking on the final year of his medical degree. He will be the first person born and raised in a Haredi community in Israel to become a mainstream doctor, and he plans to specialise in internal medicine.

Sabiner has benefited from a pioneering scheme at the Technion university in Haifa to draw young ultra-Orthodox, or Haredi, Jews from largely closed communities into mainstream education and then into the workforce.

The numbers are still tiny – about 60 out of a total student population of 10,000. “But the idea is to bring the number to 200 within five years, and to 400 within 10 years,” said Prof Boaz Golani, a vice-president of the university. “Engaging the Haredi community is important for Israel. Having a civil society where entire segments live in their own world and with little interaction with others is not healthy. It’s a recipe for tension and animosity.”

Sabiner has dreamed since the age of three of becoming a doctor. Photograph: Rami Shlush

Sabiner has dreamed since the age of three of becoming a doctor. Photograph: Rami Shlush

In 2017 the number of ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel rose above one million for the first time, accounting for 12% of the population. By 2065 they are expected to make up a third of Israel’s population.

Traditionally, Haredi men are not economically active. Many spend their time in religious study, relying on state benefits to support their large families, which average almost seven children. But in recent years the Israeli government and educational institutions have taken steps to integrate the Haredi population into colleges and workforces.

“There was a concentrated effort launched a few years ago by the ministry of transport, which needed more engineers,” said Golani. If the Technion could get Haredi students on to its courses, jobs could be guaranteed.

“We knocked on the doors on yeshivas in Bnei Brak [an overwhelmingly ultra-Orthodox town near Tel Aviv]. We found a few rabbis ready to talk to us. The idea was to take young men who had the brain and intellect to meet the scientific admission criteria, and who were not perceived as chief rabbis of the future.

“We said we would not try to force any change of lifestyle of students, such as [strict] dress codes or praying. We kept a low profile.”

The Technion team identified 37 young men for a pre-university programme run from an anonymous rented warehouse in Bnei Brak. Over the course of 18 months, teachers tried to close a 12-year education gap to bring the Haredi men up to the standard of high school graduates.

They studied from 8 am to 10 pm. “It was like a Bootcamp, very intensive,” said Golani. “But they brought from the yeshivas an ability to study hard, to focus, to apply logic, so we built on these skills.” At the end of the programme, about half were admitted to the Technion; they graduated this summer.

Bringing the students up to the required educational standard was not the only challenge. Gender segregation, a norm in Haredi communities, was a big issue, Golani said. “We told them upfront that we would not allow gender segregation on campus, no way. We suggested they arrive at class 10 minutes early and sit together, and they accepted that. We also told them that we have female professors, and we will not tell them they can’t teach certain students. They accepted that too.”

Another key issue was the use of the internet. “So each [Haredi student] carries two phones: a kosher phone, with no apps, and a regular smartphone. On that, there is an app which tracks the history of all addresses browsed and sends a report of every website visited a designated person in their community.”

Some students have been ostracised by their communities. “One girl was boycotted by her friends. Someone else told me he was hiding for years, lying to his wife and family, telling them he was studying at another yeshiva when he was at the Technion.”

The university also runs programmes aimed at encouraging Arab students to enrol. “That tends to be easier because their communities are eager to see them again top-quality education and so the community resistance is much lower,” said Golani.

It was essential to integrate “untapped resources” – meaning Arab-Israelis and ultra-Orthodox Jews – into the economy, he added. “The economy of Israel is largely based on the hi-tech sector. It’s the locomotive that carries the entire train of the Israeli economy. But we just don’t have enough people. Israel is a small country; we’re not India or China.”

Sabiner is now in the final year of his medical degree. Photograph: Rami Shlush

Sabiner is now in the final year of his medical degree. Photograph: Rami Shlush

When Sabiner embarked on the challenge of becoming a doctor, initially he faced scepticism. “I was told it was impossible for me to catch up [academically] and to be accepted, that I would never make it as a doctor,” he said. But staff at the Technion “believed in me when no one else did”.

“I was sure this was the only thing I want to do in life. I studied day and night, with a baby on my shoulder and my wife studying with me. I finished [the pre-university programme] with 99% in every field, and I was accepted [on the medical course].

“In the beginning, I kept it as a secret, only my close family knew. But then it became a known secret and I was under the microscope. In the end, 99% of people were encouraging me.”

Now that the end is in sight, he wants to encourage other Haredim to follow suit. “When I started the journey I said I don’t want to be a single episode. So I opened a group on social media telling other Haredim how they could become a doctor. Now we have 35 more in medical school.”

Attitudes were changing, he said, with more integration and mutual understanding. “People understand we’re not a bottle of Coca-Cola on a production line, we’re individuals. If you want to do medicine, you should do medicine, and if you want to be a lawyer, you should be a lawyer. And if you want to study the Torah, go for it.”

Yehuda Sabiner – Haredi, soon-to-be MD

Article by Shlomo Maital, published on Jpost.com on December 18, 2018.

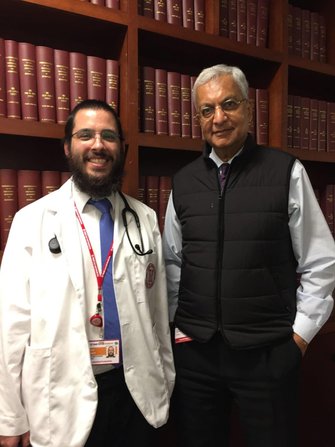

Yehuda Sabiner: Doctor in training (RAMI SHLUSH / TECHNION)

Yehuda Sabiner: Doctor in training (RAMI SHLUSH / TECHNION)

IN THE world of hi-tech start-ups, especially biotech, “proof of concept” is crucial. It means showing that an idea (device, or drug) does what it claims to do.

My new friend Yehuda Sabiner is a Gur Hasid, in the final year of medical studies at the Technion. In a few months, he will be Yehuda Sabiner, MD. Gur (or Ger) Hasidim is the largest Hasidic group in Israel and originated in Góra Kalwaria, Poland.

Sabiner is proof of concept that Haredim can become doctors, or for that matter, economists, scientists, engineers, or anything. With the ultra-Orthodox now comprising 11% of Israel’s population, and are ultimately projected to rise to one-third within two generations, it is vital we integrate them into productive employment.

Despite his crammed schedule – in addition to his studies, he works as a physician’s assistant in the emergency medicine department of Ichilov (formally known as the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center) – Sabiner took time to answer a series of questions. Here, in his own words, is the tale of his journey:

“I am beginning my final year of medical studies at Technion. I am certainly proud of the divine gift given to me, to reach the end of this long, difficult journey, with many challenges, lots of ups and downs and high uncertainty.

“As a child, young yeshiva student and as a Gur Hasid, I’ve evolved into a successful medical student about to become a medical doctor, one who has retained his Hasidic identity as a family man, father of three, with strong involvement in my Haredi community in health matters and matters related to higher education.

“I recently facilitated a conference on Haredim in Medicine, sponsored in part by Yedidut Toronto (Jerusalem). Prof. Karl Skorecki, head of Technion’s Rapaport Institute, Faculty of Medicine, and head of R&D at Rambam Medical Center, spoke at the conference. Prof. Skorecki was recently appointed Dean of Bar-Ilan University’s School of Medicine. His fascinating presentation focused on Jewish aspects of medical breakthroughs in genetics.

“Following his talk, I gave a detailed lecture about medical studies in Israel and about the role and journey of the doctor and the value-added of medical doctors from the Haredi sector.

“When I was growing up, from about the age of three, every boy dreamed about what he wanted to be when he grows up. Some imagined becoming soldiers and policemen, some wanted to be firemen and contractors. It does not matter that these dreams of small boys are of little consequence because their concept of the world is still not well-formed and they do not yet have the right perspective about the importance of various aspects of life.

“I grew up in the Har Nof neighbourhood of Jerusalem and when ill, I visited the very special children’s clinic run by Dr Jacob Schapiro, a graduate of Yeshiva University, and Dr David Matar (a Harvard graduate). These two distinguished paediatricians, with extraordinary compassion and rare professional abilities, had an excellent research lab, as well as their clinic. For me, from a very young age, they were an inspiration as role models to emulate.

“Except for them, I had no connection with any doctors; in fact, I was the first in my family to gain higher education for generations and perhaps for all time. Only lately did I hear about a distant cousin who recounted that my great-great-grandmother in Poland wanted to study medicine in Vienna, but family matters did not make it possible.

“In the first meeting with my future wife, Rachel (first of two “dates” in the shidduch or matchmaking process), I said I cannot promise to remain in yeshiva all my life, and if not, I will look into other options. I assume that all the information my future wife gathered about me during the early phase of the shidduch ”investigations” – that I was a serious Torah student in a well-known yeshiva, known for producing future rabbinical leaders – dulled the warning lights that should have been lit when I made this statement. To make a long story short, nine months after our wedding, I brought up the subject of becoming a doctor. In any event, for many couples in the Haredi society to which I belong, this revelation could have been a sufficient trigger for breaking up the marriage, especially at such an early stage. And to judge by the intensity of the tears and distress I caused, I think we were not far from it.

“To my good fortune, after the ‘Big Bang’ my dear wife approached me and said that she was impressed by my sincerity and purity of intentions and that she knew I would not relent unless I achieved them. So, she gave her consent to my medical studies, subject to the approval of an important adviser respected by both of us.

“The hardest part of my studies was the machine [preparatory course], and especially, language studies and math. While for physics, every law was explained in-depth, in math, because time was so short, we were bombarded with a multitude of rules without real explanations, and as a former yeshiva student who was accustomed to spending hours debating the logic of laws, this was very hard for me to digest…but in the end, I succeeded in this, too. Half of the machine participants dropped out.

“I was in the first such machine class at the Technion for Haredim, so there was a very little past experience for the Technion to draw on about how to realize their students’ full potential. Many dropped out, after seeing their grades in the first trimester’s exam, the first of three such exams – and they panicked. I don’t know what has become of those who dropped out but I am certain some of them could have completed the machine successfully if they had continued and invested their full effort in it.

“The toughest part of my studies was, as I mentioned, the machine and catching up on math. At the end of a long day of studies, stretching into the wee hours of the morning, my wife would sit with me and help me to understand my homework. Parenthetically, Haredi women finish high school with the equivalent of at least three credits of math, English, history and other subjects.

“At this stage of my studies, while my wife was in the middle of her own intense studies as a practical architectural engineer and interior designer, we became parents of a baby girl. Nonetheless, she was extremely dedicated to actively helping me as I caught up on very basic studies, which were very challenging for me.

“So far, in all my medical studies, in various departments and specialities, I was most fascinated by internal medicine; it ideally combines the anamneses [intake] and diagnosis, a holistic view of the patient and synergy among the various organs of the body. (Note: Every internal medicine department in Israel is severely understaffed.)

“I think one needs to know how to continually learn, and not to try to escape to some super-specific sub-speciality where you lose the unfathomable beauty and major challenge of sleuthing until you find the right diagnosis and help with a cure or relieve the patient’s symptoms.

“I hope internal medicine will be reorganized and that specialities in Integrative Medicine will be created to train ‘case managers’ for multidisciplinary ailments throughout the hospital. In other words, create a different discipline instead of one that at present is unattractive.

“We indeed live in a time of major change in the Haredi community. It’s hard to predict, but we see more and more mainstreamed Haredi men and women, slowly but surely integrating into many quality occupations, as a result of some individual initiatives. It is noteworthy to mention the contribution from two organizations that catapulted the Haredi academics several light years ahead: Keren Kemach (Kemach Foundation) and Yedidut Toronto.

“A few years ago, I myself established an organization called Haredim in Medicine, which aims at increasing awareness and assistance in integrating Haredi men and women in medical studies in Israel. Today, we can safely say that the numbers are growing and the trend is upward. Slowly, I am broadening the organization’s horizons to foster research excellence among future Haredi doctors, to create interfaces and to help solve medical, cultural, and halachic problems of Haredim, through research and awareness.

“There is much more work to be done in this area, but I am certain that with G-d’s help, we will see a better world, where the best of our Haredi boys and girls will join the vanguard of science, economics and medicine, in Israel.

“EIGHT YEARS of intense study poses extraordinary economic challenges to a family of five. Our immediate family helps with preparing food and looking after the children.

“The State of Israel as a nation cannot forego the professional cooperation of 11% of its population (Haredim). It is natural that in such a large population, splendid medical clinicians, great inventors and developers of medicines, successful managers, etc. can emerge.

“The Haredi community, with its halachic and cultural complexity, has developed over time unique medical challenges that demand treatment and solutions. Sometimes increased awareness is needed, and other times, solutions and compromises. But it is clear, all of this will be done far better and more efficiently when there are those closely connected with the two interfaces, medicine and Haredim, through community medicine.”

FOR EXAMPLE, Sabiner provided me with data showing that only half of Haredi women over 40 receive regular mammograms for early detection of breast cancer, compared with 80% of non-Haredi women.

According to Nitza Kasir and Dimitry Romanov, of the Haredi Institute for Leadership Research, Haredim will comprise almost a third of Israel’s population by the year 2065. And unlike other forecasts, demographic projections tend to be accurate. The inexorable conclusion is that Israel cannot afford to neglect Haredi minds – those who do not find their calling in yeshiva but seek secular education.

My S. Neaman Institute colleague Dr Reuven Gal, formerly an IDF chief psychologist, heads a successful program, “Shiluv Haredim,” which integrates Haredim into society and the workforce. In his recent study, Gal observed that some 30% of Haredim said they would be “happy to see, to a greater extent, Haredim studying in higher education” and a quarter of Haredim are not opposed to “core studies” (math and English) in Haredi schools.

For those who say this is still a minority of Haredim, Gal responds that “only 15 years ago those responding positively to similar questions were one in ten, or even less.” Change indeed is underway among the ultra-Orthodox.

Dr Gal told me, “I met Yehuda in the summer of 2012, toward the end of his first year of studies. He was at that time the first Hare- di student aiming at graduating from medical school in Israel. I must admit – I was not 100% sure he would succeed in reaching this goal. But he was. The list of the obstacles and difficulties he had to overcome, just to reach that point, and those he had yet to face was endless. But he was, in his shy and quiet way, so confident!”

“At that meeting – with several other Hare- di students at the Technion – Yehuda made a statement. ‘We shall become a model for much Haredi youths. We are going to speak about the Technion in our synagogues, we’ll tell the others at the Kollel (yeshiva for adults) that by earning an academic degree they will gain a reputable entry-ticket to quality jobs and thus will be able to make a living to support their families – and at the same time, not to forsake their faith and way of life.’

Sabiner poses for a photograph outside the of Rapaport Family Medical Sciences Building (RAMI SHLUSH / TECHNION)

Sabiner poses for a photograph outside the of Rapaport Family Medical Sciences Building (RAMI SHLUSH / TECHNION)

“I salute Yehuda,” Dr Gal said, “for his persistence, his devotion, his faith. He is a Nachshon, a spearhead in front of a huge camp of Haredim who yearn to walk the same road but are frightened. Men like Yehuda give them the courage and the example that they can do it as well.”

In an article about Sabiner in the British daily The Guardian, Technion Vice President Boaz Golany noted how Haredim in the Technion machine studied long hours, from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. “It was like a boot camp,” he said, “but they brought from the yeshivas an ability to study hard, to focus, to apply logic; so we built on these skills.”

It all began with a program called Hala- mish, in 2007, and gradually grew, with financial support. Backed by Iscar CEO and philanthropist Eitan Wertheimer, Halamish supported pioneering Haredi students seek- ing to learn a profession.

Today, after 18 months of machine studies, Haredim who never studied science and English and have only learned rudimentary mathematics are brought up to speed and the majority are accepted to the Technion. Graduates now work as engineers in hi-tech companies and some are pursuing advanced degrees.

I have spent the past 40 years at the Technion and have admired, studied and recounted the amazing hi-tech contributions of its graduates and faculty members, to Israel and the world. But there is a special place in my heart for those bold Technion leaders and instructors who undertook the impossible – taking in ultra-Orthodox men who know no math, English, physics or chemistry, and in 18 months bringing them up to speed sufficiently to enter the Technion. And, of course, it is these bold, pioneering Haredim themselves who aspire to college degrees, who deserve the warmest embrace.

Impossible? For example, I once wrote about A., who graduated from Technion as a civil engineer. In his first machine class, he raised his hand and asked the instructor, what is that cross you wrote on the board? It was an “x” and the teacher was explaining algebra. A. had no idea. Many years ago, the historically black (African-American) colleges in the US raised funds with a powerful slogan: “A mind is a terrible thing to waste.” This applies to the growing ultra-Orthodox community. These sharp minds honed on Talmud studies are a priceless resource.

Lately, Yehuda told me about his second day at a family medicine clinic in Bnei Brak, a mostly Haredi city, the start of a monthlong assignment. He was hesitant to be assigned to Bnei Brak, not knowing how the people would react. After all, patients tell doctors their most intimate secrets and issues – and he, Yehuda, is a member of their community – perhaps even someone they meet on the street. But, he said, after their initial surprise at seeing a Haredi physician, patients’ reactions were highly positive and fully cooperative.

Yehuda Sabiner, Gur Hasid, soon-to-be MD, is a precious proof of concept. And many others will follow in his path.

First Israeli-Born Hasidic Doctor Blazes New Trail in Medicine!

Dr. Yehuda Sabiner.

Dr. Yehuda Sabiner.

The new doctor wants to encourage other members of the religious world to help their communities by entering the field.

Dr. Yehuda Sabiner is the first Israeli-born member of the ultra-Orthodox community to graduate from medical school. His success, against the odds, is encouraging many religious and non-religious people to reach for their dreams.

He was inspired by two outstanding physicians as a young child, deciding at an early age that he wanted to be like them as an adult, even though there had never been an ultra-Orthodox doctor in Israel before.

“When I was a child, I had in Jerusalem two very special pediatricians…[who] were both very special in their profession but also in terms of being a mensch [a good person], in compassion and empathy to their patients,” he told Jewish Home LA. “But as I grew up, I also understood that the field is very attractive…you have to be very smart to understand this stuff, and you must be curious about it, and it’s one of the fields…you can provide so much help and chessed [kindness] to members of your community, to human beings.”

As a child, Sabiner received an ultra-Orthodox education as a member of the Gerrer Hasidic sect. This meant that he studied Torah full time and did not formally learn math, chemistry, English, or physics. He did, however, learn discipline and how to study intensely for as much as 14 hours a day.

At 16 years old, Sabiner and his peers embarked on a challenge trying to “study[] five hours in a row without going to drink, or to talk, or to the bathroom.”

Sabiner credits his Jewish education for “exercising his brain” with deep Torah studies that taught him to ask questions and find solutions.

“When you see a case of a patient, a medical case, you always try to challenge the first diagnosis, you try to challenge people who said something else, to see, is it still possible? Still true?” he told Jewish Home LA.

In 2011, he was accepted into an 18-month special program at the Technion designed to fill in the educational gaps of intelligent and determined religious students in order to facilitate their rapid entry into conventional degree-track higher education. Sabiner was one of 67 students accepted into the program and one of only 17 who completed the rigorous course.

Today, the graduate of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology Rappaport Faculty of Medicine and doctor of internal medicine says, “I enjoy the big picture aspect of it and how it’s multi-disciplinary.”

The doctor is soon starting his six-year internship at Israel’s largest hospital, Sheba Medical Center in Tel Aviv, according to the Jewish United Fund. His goal is to give back to his community, which supported him despite his unconventional career path.

Encouraging others to pursue their dreams and potential, Dr. Sabiner said, “There are very, very, very talented people among us—boys and also girls—and they should get the full potential of whatever they want to be. I really don’t care if it’s as a rabbi, a rosh yeshiva [head of a religious institution], a lawyer, a doctor—any way you choose, you should do the best you can.

“I am far from being a genius,” he told Jewish Home LA. “It’s not easy, it’s not easy for anyone, especially someone who has never studied general sciences, but still it is possible, and once you know it’s possible, you can do it.”

In addition to being a doctor, Sabiner, 29, is also founder and chairman of an ultra-Orthodox professional organization called Haredim in Medicine, which helps religious people join the medical field by helping them overcome cultural barriers.

Thus far, 35 ultra-Orthodox Jews are attending medical school in Israel, following in Sabiner’s footsteps.

Israel’s first home-grown ultra-Orthodox doctor in midst of coronavirus fight

Dr. Yehuda Sabiner. (YouTube/N12/Screenshot)

Dr. Yehuda Sabiner. (YouTube/N12/Screenshot)

Dr. Yehuda Sabiner started his internship at the country’s first dedicated coronavirus ward.

By Paul Shindman, World Israel News.

Israel’s first home-grown ultra-Orthodox doctor has landed in the trenches of Israel’s coronavirus fight, Channel 12 news reported Saturday.

On the first day of his internship at the Tel Hashomer hospital near Tel Aviv, Dr. Yehuda Sabiner, 29, said a senior doctor called him over and said the department was transitioning to become Israel’s first ward dedicated exclusively to coronavirus patients.

“She said I could refuse,” Sabiner told Channel 12. “I thought once or twice and told her I’m OK with that, let me just ask my wife, who said to me straight out wherever you are, whatever they ask of you that’s your job.”

It turned out that 70 percent of the patients in Ward C, the corona ward, are fellow members of the ultra-Orthodox community from the hard-hit city of Bnei Brak and Sabiner knows some of them personally.

Emerging last Wednesday after spending several days in the ward to minimize exposure to others, Sabiner said his last overnight went well and he was excited to be able get a special short leave to go home for a short time to celebrate Passover with his family.

“There was also a bit of drama during the night,” Sabiner said, during which doctors needed to stabilize some patients and “for the meantime to defeat the angel of death.”

As a young child Sabiner was so impressed with his family doctor he made his mind up to make it his life goal to become a physician.

In his youth, he studied Torah all day, and when he told his rabbi his goal was to be a doctor, the rabbi’s response was he needed to see a psychiatrist, Sabiner recounted.

Sabiner said his rabbi told him, “It’s not realistic, you won’t be accepted, you are unable, you can’t go in opposition to your community.” However, he persevered and became the first ultra-Orthodox Jew to come out of Israel’s yeshiva world and graduate from medicine, getting his degree from the prestigious Technion University in Haifa.

All other ultra-Orthodox doctors in the country got their medical degrees abroad and immigrated to Israel, Sabiner said.

When the coronavirus outbreak turned serious and his children’s school was still holding classes, Sabiner called the principal and explained the gravity of the situation after which the school closed its doors.

As the outbreak worsened and the religious community was still not fully accepting health directives before the Purim holiday, Sabiner arranged to meet Rabbi Yitzhok Zilberstein, one of the more prominent and respected leaders in Bnei Brak.

After only five minutes of explanation, the rabbi issued “a very extreme proclamation” to help keep people at home, Sabiner said. “If that ruling hadn’t come out in time, the catastrophe we are in today would have been much, much, bigger.”

Sabiner will not have much time off in the coming months. With its dense population and tradition of group prayers and large gatherings for both weddings and funerals, total closures were only imposed after Bnei Brak became Israel’s most infected city.